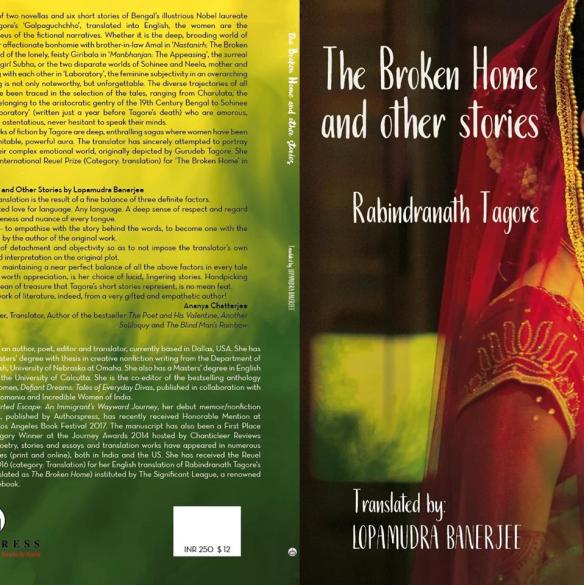

Trapped

(image source: Indiawest.com)

(image source: Indiawest.com)

(1)

My name is Rani, the Queen. But no, in this birth, the Almighty did not grant me a palace, a king to dote on me, minstrels and servants to shower their lavish attention on me. The blessed people of this world see us among them, follow our dance moves, listen to the claps of these hollow hands that earn us hungry stares, loud jeering and the papered notes of twenty, fifty or hundred. Our loaded mouths cannot contain those filthy curses that our forefathers might have saved for us, or for our wretched birth-parents for bearing progeny like us.

It might have taken some nano-seconds for the doctor delivering me, sucking me out from my mother’s cervical path to declare my sex as that of a boy. A boy, a real boon to my family bearing the baggage of five girls, girls who were like bolted doors, dark and choking like the last accursed night in the family’s small,cramped living space which housed them all. The familiar space where they would find themselves every dawn, at the edge of their sleep, damp, dilapidated, like the last dying embers of a patriarchy they clung to.

“A boy at last! God is not so unkind, after all, isn’t it?” My joyous father said, clasping my frail mother’s fingers. My mother looked at me, her much-awaited newborn, her face pale, devoid of blood. After twenty sickening hours of a difficult labor which had almost killed her and me, her pre-term baby boy, her hands touched my lips, my mouth, trembling with my first cries.

After all these years, their prayers had borne fruit, no matter how late for my middle-aged parents. My father burst out in staccato coughs and laughter as he examined my body from head to toe. A boy at last, a boy who could walk beside him step-by-step in the morning trails watching over the harvest, a boy who could smoke like him with insolence, be his second voice in the flim-flam of everything said. A boy who could pee with him in the street corners while returning from their local market, a boy with whom he could even trash-talk about women and their boundaries.

It was the auspicious eve of the Baisakhi. Virgin dewdrops had glistened on faith’s leaves; my parents brought me home. In the years that followed, they expected me to be snugly fit into the metric lines of a cherished boyhood. They had endearingly named me ‘Veer’, their sher puttar, their tiger cub drinking the milk of human kindness. I was nibbling on the dried-up bones and marrows of a patriarchal home with minimal resources in the small village of Punjab, my birthplace.

They had named me ‘Veer’….Ever since I can remember, they called me Veer Puttar, the brave boy, the sure remnants of a masculine pride. They chased my naked body all day in the open courtyard till I was all of four or five, after which my favorite drapes were my Amma’s soft, unstarched cotton salwar kurtas or my sisters’ flowing, silken dupattas (scarves).

“Shameless boy! I will beat you to a pulp till you turn into a man! Look at yourself in the mirror, your robust arms and chest, your male organ, which ought to be your pride, but here you are, making my head hang in shame! Is this why I had craved for a son of my own after five dark, worthless daughters?”

My father’s slaps resounded in the cramped room where me and my sisters huddled together like fallen angels. I was all of ten, tall, lanky, yet frail, feminine, decked up in a polka-dotted frock in pink and white, the only fancy attire that the youngest of my sisters had. In my lips, the cheap pale lipstick gleamed, that of one of my sisters’.

I was more of their own kin than of my father’s, floating in the dainty dreams of the kind of things the girls of my familiar earth did. I was hooked to the things they wore, the cheap rubber dolls they played with, the cloves they chewed on for a fresh, minty breath, the dough of chapatti they kneaded. In my furtive mind, I had craved to flaunt my flowing tresses like the braids my sisters roamed around in, rather than tying them all up in a turban which was the pride of our cherished ancestry.

“I know why you look so happy today. You are wearing your favorite nail polish, aren’t you? The groom’s family came to see you and approved the match. In a few months’ time, you will be gone from our house. Can you please apply the nail polish on my fingers, badee didi?” I asked my elder sister. I was all of twelve, and she rolled her eyes in a vain anger.

“Baau jee (father) will kill us if he knows of this!” She replied.

“Please, badee didi. Consider this my last request to you.”

The spirited coatings of deep pink adorned my slender, girlie fingers, an unpardonable aberration, a sacrilege to my masculine body, trembling, dying with eager feminine wants. The news spread like wildfire in a congested home where the baggage of such ‘dirty’ secrets were too heavy to bear, and our father soon confronted me, fuming with rage.

“I will teach you a lesson today that you will never forget in your entire bloody life, you scum of a boy!”

He caught one truant hand of mine and dragged me to our common toilet, shoving me towards the old, worn out latrine that we all used, pushing my hand with all his might towards the latrine reeking with the odor of human shit. The hand had the fresh coating of the pink nail polish and I had to pay the price for it, as vomit pushed out of my esophageal tract. I threw up in the toilet, the vomit of years of disgust of being their puppet son marionetted at the whims of their gendered wants.

Before my elder sister’s wedding in the house, my father slapped me time and again, whipped me, coaxed and cajoled me to be that ‘Veer Puttar’ whom my parents were eager to show off to their new relatives, the brave boy who would fend for them with all his budding manliness. I was in dire need of turning into the chivalrous brave boy serving as the perfect antidote to their lives burdened with the presence of four more frail daughters, apart from the one being married off.

In the kitchen where our eldest sister Jaspreet kneaded the doughs of chapatti with our Amma, where my younger sisters cut the vegetables and helped Amma in grinding the masala for the curries, I was denied access as our father took me out to the fields, to the bazar, to the tailors and other places to run errands and most importantly, make a ‘man’ out of myself. One night, just before Jaspreet’s wedding, our youngest sister whom we endearingly called Tanu came up to me.

“Veeru, I am practicing a dance number for Badee Didi’s wedding. You dance so well, please be my dance partner; the groom’s family will be much impressed.” She whispered in my ears.

I looked curtly at my parents, unmindful at the moment, occupied with their nightly chores of dinner. “Dance”, I muttered to myself, the fluttering of my feminine wings which my family wants to strap shut. I was both sought after and called names in the village school I went to, for the swaying of my hips and the practiced curves which defined my body, by the time I grew into a teenager.

The boys at the school would look with pronounced pity when I sat, numb, trembling like a timid girl when they pounced at each other like street dogs, wrestled with each other to suck out the little things that mattered to them, but left me unfazed. The girls didn’t have much clue what to do with me. I was on one hand, a shadow of their own slain selves, dying to retain their mirth. On the other hand, I posed to them an unknown threat, the threat of hanging like a loose flesh somewhere in between the soaring masculinity they knew of and learnt to admire, whatever their vices, and their own random feminine musings.

For me, the girls and I had the same fate, that of cuts, bruises, mistakes and the assurance of a silver lining somewhere, probably in another birth if they could swallow their legitimate femaleness, and I, my illegitimate one, like a bitter pill in this lifetime.

*****************************************************************

For days, I weathered the danger of practicing the dance moves with my sister Tanu in the small grassy patch outside our home at odd, uncertain hour. For days, I walked past the same fields and the same dirt roads of our village with my father, while breathing hard against the terror of suffocation at school. And then, the wedding day of our elder sister Jaspreet approached. She sat, demure, bewildered at the decorated marriage altar inside the holy shrine, decked in her bridal wear and the huge nose-ring, an heirloom gift from her new-in-laws, and the groom looked at her with those devouring eyes. Would she endure the same fate as my mother did within a few years of marriage, giving birth to one girl after the other, walking on the thin line between acceptance and abandonment? I wondered while the rituals continued. My other sisters, her close siblings looked at the scene, smiling with hollow admiration.

“Jaspreet is a bit fair complexioned than our other daughters, I am relieved she could still stand a chance to win a family for marriage. But what will happen to our other girls who are way darker?” Amma whispered in our father’s ears.

“Just wait for a couple more years so I can sell of a few more assets of mine, and take a few loans from here and there to manage their dowry. Whosoever told you to give birth to so many girls, in the first place? Thank your stars, woman, for I didn’t kill any of them as newborns, like many us I know did….for now, just keep an eye over Veeru…watch him like a hawk, so that he doesn’t imitate his sisters and make a worthless fool of himself. He is our only hope in our older days and he must learn to live up to his name!” He replied.

Amma nodded her head. I could see her trembling, her tired, weathered frame, sometimes in tune with my sisters, sometimes with my own, now ready to strum along my father’s wants. She didn’t have any other choice; she had to ‘live’ the bare remnants of her life with her man in that humble house which was her only shelter.

Outside our small home, the members of two families congregated to bless this union, following the pious prayers. My sister Tanu and I swayed and moved our bodies in sync with the loudspeaker which nearly burst out with the froth of Hindi and Punjabi films songs and folk music. We were celebrating the hour of a holy ritual amid our happy tears, the claps of my girl-like hands mingling with those of my other sisters who joined us. We gyrated our hips and twirled and swirled to the beats of the dholak, relishing the music and the fireworks, the merry moments of a short-lived festivity.

At the wee hours of the night, when most of our guests were gone, following the fireworks, the food and the ceremony, the man who played the dholak, a sturdy middle-aged man came up to me and suddenly held my hand.

“Oye puttar, I noticed you dancing so skillfully with your sisters and the others in the crowd. There is something very different in your body movements, in your eyes and your face. How old are you, boy?” He asked.

“I will be thirteen in the coming Baisakhi (New Year) in April.”

“And your name?”

“Veer, you can also call me Veeru like my sisters do.” I said, shuddering at the touch of unknown hands.

“Veer puttar, you are anything but a twelve-year-old boy of your age. I have seen quite some boys like you in my life, trust me, you are God’s special gift. Only you have to understand and acknowledge it, and put your talents to good use.”

“How can I do that?” I asked. I looked into his eyes, brimming with an eagerness to explore things about myself which I never dared to unravel before.

“For that, I am there to help you, if you can only trust me and contact me, any day you want. My name is Manohar. Here, keep this paper with you, it has my details, my address and phone number. I am all over the place in North India, more so during the wedding seasons. But once you call me, I can tell you where you can come to meet.” The man replied, handing me a yellowed, crumpled paper, which I held in my fist, my first gateway to a wonder-laden universe which had waited for me.

(2)

“Dear Baau jee and Amma,

I know by the time I will be gone from your house which has also been my home for all these years since my birth, it will be evening and both of you will be done with most of your daily chores. You might be done milking the only cow you have, after selling off the others for Badee didi’s wedding and for trying to gather some money for my other sisters’ dowry. Baau jee might be done with his habitual trips to the fields and his daily inquiries of the whereabouts of my sisters. He might have already seen them pirouetting by the open courtyard, lighting a diya around the altar of the shady Tulsi plant, praying to Goddess Tulsi for a life of peace, prosperity and fertility in a new home that Badee Didi has found for herself.

It will be the same evening today when you both will stumble on this letter with the crickets chirping all around, with the chapattis being made in the stove. You both will see the same crescent moon peeping from our window-grill (or, will you?) yet it will be a different evening for me. This evening, I will be long past the familiar miles of our neighborhood, past the mustard fields, the tractors and the bullock carts, past our small, smelly train station. I will board a train taking me to a city, a destination where I might rediscover myself and know what I can really do in life rather than trying, in vain, to become the veer puttar, the brave boy of the family which I can never be.

I know only too well how ashamed you feel, Baau jee, every time you summoned me in the house or took me outside to do ‘manly’ things and realized I was incapable. I know how embarrassed Amma felt when she first discovered my keen interest in the kitchen, in kneading the doughs, in cutting the vegetables, frying the onions, grinding the masala. I remember how annoyed she was when she first caught me in the act of trying to wear her blouse with the only fancy bra she had (and yes, I knew about these womanly things only too soon from my sisters). I shudder thinking how desperately she wailed when you meted out those extreme punishments for me, Baau jee, for trying on the ‘ladkee walee harkatein’ (the girlie’ things). I know how hard she has prayed every day to the Lord so that the ‘man’ inside me comes out, not as much for her own sake, but for your satisfaction, Baau jee, so that she can stop cursing her womb for bearing a boy, who is more of a girl than a boy.

Let me tell you one more story of mine that just happened a couple of day before Jaspreet’s wedding. It was late in the afternoon when I was writing my Hindi exam papers in school. Everybody around me was in a hurry to finish the papers. My hands trembled and sweated, as they always did when I was nervous, and I was racing against time to finish the last big answer, and then I felt the sudden lull in the air with the music of a popular Punjabi song echoing from a loudspeaker quite some yards away. My mind struggled to answer the paper with full devotion, while my body caught the rhythm, the music and the language of the song every time the echoes got louder in the classroom. It was like the first blood that Nitu bled a year back, which she described to me like an inner flood, which she had no control of. I wanted to bleed vermilion like her at that very instant as my feet tapped vigorously to that known rhythm. I wanted to chop myself into thousand rainy blood drops as my shoulders and hands swirled in a queer motion, all the while striving to finish the paper.

“How much is left, Veer? Have you finished? The warning bell has rung already, puttar.” Our Hindi teacher came up to me and looked into my eyes with a strange curiosity.”

“I just…I just…have a bit left.” I stammered.

“Ok, I give you a grace period of five more minutes. But be fast.” He whispered to me, and hurriedly collected the papers from all my other classmates.

In a few minutes, when they were gone, my hands trembled again while submitting him my paper, still unfinished. Right then, he grabbed one of my wrists and looked at me with quite a menacing smile as he said: “Wait for two more minutes, I am very curious to know how you do the things that you do. You have to tell me today.” He headed straight to the classroom door and bolted it carefully.

“Sir? I did not understand!” I was perplexed.

“I am dying to know how you walk in those girl-like steps, how your lips always quiver with that girl-like fragrance….I want to know…I want to know what you hide under this ironed khaki uniform that you wear to school every day.”

….I stood there, transfixed, dumbfounded. He now groped my trembling body and started unbuttoning my shirt, kissing me with full vigor, panting, sweating all the time. I whined and grimaced under his tight grip. As a last recourse at resistance, I somehow managed to dash his head against a wall while with my big fingernails, I kept scratching his body till he bled. Those were the same fingernails that bore the punishment of wearing a pink nail polish some days back.

For the first time, while I managed to open the bolted door of the classroom and come out in the open air, I felt proud of those fingers, those sharp, dainty, girlish fingernails. I felt proud of what I did at that instant, looking at my shirt, unzipped, partly covering my queer body. From that day, I had stopped my pursuit of being a man altogether, a manhood that you coaxed me, cajoled me, assaulted me to possess. I understood that a man can be more basal and gross than a hungry animal in search of his prey, and that being a girl trapped in a man’s body, I can at least try to be a worthy human, weak, vulnerable, but saner than the men folk that I have seen, swarming around me.

I am rather happy today, Baau jee, that I dared to transgress my boundaries and dance with Nitu and the other girls at the ‘sangeet’ festival of Badee didi Jaspreet’s wedding. I just got to know that it is not for a reason that the Almighty has made me in a different clay than he has made other boys of my age. I just got to know that he has created me with something unique and special, and I am going out to explore what that really is.

It will be a new place, a new city where I will have to fend for myself, but there will be someone who will help me. However, right now, I cannot disclose any details to you as I leave. Amma, I know you will shed tears as you will know that I am taking this plunge, and try looking for me, in vain. Baau jee will again rebuke you for giving birth to one more useless child. As for my sisters, I know they will miss me and the bonhomie we shared for some days, shed tears, and then the swift current of the waves of time will overpower them, in their pursuit of being the good daughters, good daughters-in-law, good mothers, rather than anything else. I cannot be any of these, but still remember you had gave me birth with much toil and much love, Amma. Don’t worry about me roaming around the unknown streets like a beggar, for I managed to take the money that I got for my dance performance at Jaspreet’s wedding. The silver karaa (bangles) in both my hands might also be of use, if needed later. For now, I already said I have someone who can help me find food, shelter and my own pehchaan (identity). I am dying to know what it really means, in this big world outside our village.

Paaye lagoon…I bow my head before your feet.

Yours’ ever,

Veer.

(3)

The paths that went all the way from my small native town in the district of Jalandhar, Punjab to the stunning garden city of Chandigarh to the blinding maze of the overwhelming city of Delhi have been crooked, murky. I have lost myself in this arduous journey and rediscovered myself zillion times. Would I dare to call it an odyssey of my life twirling in a spin and disrobing all that you had taught me since birth to hold dearer than my own life? I was hungry like a street dog, yet desperate to flee from the life in the village which was really never mine. I had without any qualms, thrown away the saffron turban which hid my wild, wavy tresses, and came out in the open with my long, unruly mane, thicker in volume than all of my five sisters.

I purse my lips as I remember the train that took me to the alluring city of Chandigarh, the first big city which I was waiting to encounter that day since years…When I fished out a pack of red bindis and a red lipstick from a ladies’ bag and wore both the red bindi and red lipstick, seated in the general compartment, I had seen it all– the inquisitive, even lusty looks of fellow passengers inside the train who seemed like dying to devour the guarded secrets of an effeminate body, dressed in male clothes.

“Where are you going to, dear? Any adult family member with you?” The ticket checker approached me with a queer look of disbelief in his eyes.

“No, I…I am traveling alone…to Chandigarh. A relative will receive me from the station.” I had stammered.

“And your ticket?”

“I…I didn’t find the time to get my tickets, the train had come to…to the platform…and I ran to board it…but I have this with me, you can keep it if you want.” I stammered some more, and got out the silver bangle of mine from my right hand and handed it to him. My heart would jump out of my rib cage, I felt, leaving me a piece of dead meat. But to lessen my sense of terror, he glanced quickly around us to see if there were any intruding eyes watching over the scene, grabbed it and placed it in one of his pockets within seconds.

“Chandigarh is coming in another five-ten minutes. Utar jaa jaldi, varna dekh loonga (Get off from the train quick, or else you will face consequences)” …the train had halted abruptly in a level crossing…he had shoved me out of the train, in the face of an unknown stop, and in the silhouetted darkness, all I knew was that I had to somehow push my way till the apparent destination.

Besides the two silver ‘karras’, I had limited money and resources inside the ladies bag which I had coaxed and cajoled Neetu, my youngest sister and my partner in dance and other such crimes to give me as I eloped from home. I knew the money would be enough to feed me for a week at the most, but I couldn’t care less…All I cared about was to meet Manohar jee, the dholak wallah, the musician at Chandigarh station who had promised me a life of gay abandon which would be at my fingertips if…if only I could train myself to utilize the ‘skills’ that God had bestowed me with since my childhood. From the unknown level crossing to the farthest end of platform number 1 of Chandigarh, I ran through a long stretch of uncharted miles relentlessly, panting like a wounded beast and finally stumbled on Manohar jee, just on the verge of passing off. I groped in the dark for that one elusive word, pehchaan, ‘identity’. I earnestly prayed to God that I would be able to find it some time soon.

“God, you are looking so pale and sickly! You must be exhausted from your journey. But you look so charming with the bindi, my dear! Come, I will feed you some tasty onion pakoras (fritters) from one of these stalls in the station.” Manohar jee placed one of his hands on my shoulders, while I was still panting. I had forgotten to remove the bindi from my forehead, being forcefully shoved out of the train, I remembered then. His touch, his stare was reassuring, as I relished the taste and aroma of street food, quenching my parched lips and my hungry stomach.

“But where will we go from here? Where will you arrange for my stay now?” I couldn’t help asking.

“Ha ha ha ha! Poor one, you are so impatient! You will get to know everything dear. I am here to take you to one of those very interesting places which will give you shelter and train you for a bright future. You will see a few other young boys like yourself there, who crave to do the same things that you do.” He laughed and revealed, with a naughty glint of secret playing in his eyes.

(4)

One of these days, I had been made to sit with a fake smile dangling in my lipsticked mouth, holding in my cold, trembling hands a cup of coffee and a lavish chocolate pastry. I was with a young, bold girl who approached to interview me for a TV channel.

“What do you even want to know, girl? You are one of the enlightened lot. You already know how our clan is made, how they thrive and how they die unnoticed, every single day, don’t you?” I asked her.

“Yes, I have read about lives of people like you in bits and pieces in newspapers, magazines… but tell me about you, your journey, how you landed in Delhi, what made you stay on in the nation’s capital. Did you ever visit your native land after ending up here? Did you ever meet your family again?”

She had a smart, polished urban accent and the nonchalance that seemed too typical of reporters of her ilk. Her questions started killing me, one stroke at a time, but the fake smile in my lips was pasted intact. Over the years, my life had taught me that sarcasm was the antidote to all my pain.

What would I tell her about how I started my life, cooped in an almost ramshackle den with nine other boys who had eloped from home from all parts of north India, just like I did? All of us had more or less the same stories, leaving our homes with the assurance of finding a new meaning of our lives, , egged on by Manohar jee, the charmer. In the days and years that followed, we became family, ‘soul sisters’, we used to call each other.

Rupa, Lakshmi, Radha, Manju, Nadira, Munni, Nargis, Paayal, Monalisa and myself, Rani, we were rechristened with new names. We had been adept at the skills of drumming, singing recycled Bollywood songs, dancing like there was no tomorrow. Day after day, we danced to the whims and the cryptic tunes of our mentor, our nurturer Manohar jee, who would feed us good food and buy us decent clothes if we relented at his cat-calls and stripped ourselves of our clothes for his own sick carnal pleasures. It did hurt a lot, and I threw up a lot, like I use to do, back at home. But after a long while, it all subsided, the sudden shock and stupor of being initiated into the ‘hijra’ rituals by a queer-looking woman in the presence of Manohar jee, the excruciating pain and terror of getting castrated by a quack in a shady den which Manohar jee had called the ‘doctor’s clinic’, an ordeal in which most of our lot was at the threshold of death for days on end. But could death come so easily to us, anyway? We had to live on for many years after this forced death of our old selves. Our resurrection was celebrated with much pomp, as it ensured that Amma, our very own eunuch guru would be hugely benefited from our services, and that Manohar jee would get a decent sum every month from her.

“Didn’t the ten of you suspect that Manohar was an agent of this eunuch guru since the day he coaxed you into all of this? Couldn’t you do anything about it, take help of the local police, or go back home, to your parents? Don’t you wish to see them for once, after all this?” The young girl sounded more inquisitive than needed, holding the mic, incredulous, instructing her crew to shoot my profile from various angles. The questions gushed out of her mouth like darts that didn’t know where they would hit. Unlike my old inmates scattered in various parts of Delhi, Haryana and other places, who I know, cuss and break down, I had been an expert in restraining my mad rage and sobs now, especially when confronted by anybody from the mainstream of society. All I needed to cool my senses was a cheap beedi tucked in my mouth and its smoke, spiraling in the arid air around.

“Home? What’s even a home? My parents have disowned me long back, in the years of my growing up. Would I go and complain to them what Manohar and Amma did to me, to all of us? They would spit and puke in my face in the presence of our fierce relatives and have me stoned to death in front of the village panchayat.” I remember the words uttered by Rupa, our oldest inmate years back, as she had hugged me, Payal and Monalisa, the newest entrants at Amma’s den, shivering, shell-shocked at the revelation of the new life of a eunuch that awaited us. We all had wanted to go back home at some point, but we knew we were at the point of no return. Yes, she had been driven out of her home somewhere in Punjab and abhorred the word ‘family’. Three of the others, Munni, Nargis and Nadira had drugged themselves with the lure of ‘ganja’ and homosexuality which would help them conveniently forget their past lives, whatever they were, in whichever part of the world.

As for myself, Rani, the more blessed ‘queen bee’ as Manohar jee had called me, the only intoxicant that glued me to this world was my inborn talent of dancing. My inborn love for dance had made me sever my ties with my parents, and after a couple of years, compelled me to change my moorings from Chandigarh to Delhi. There was great potential to earn much more in the big city, and my dancing skills would fetch him good money not only at marriage functions, or at homes after the birth of babies, but through extra gigs, like joining in the local bar at Dariya Ganj as an extra with the main bar dancer, or pleasing his gay clients at cheap, stinking hotel rooms near the Chandni Chowk or the NCR area. And as always, he gave me a meager percentage from the earnings, as I had sold my body and soul to him years back, when I was still Veer, a naïve, unassuming teenager from Jalandhar.

For quite some time, the flow of my life had assumed the form of the slow-moving, permissive water-body of the Yamuna, on the banks of which I now shared a small one bedroom flat with Rupa, who had come to Delhi a year after I arrived. Sometimes we go out together to earn money, sometimes I roam around the uncertain miles of the city alone, in crowded buses and trains, in the bustling Delhi metro, being one of the many thousands of eunuchs making a living in the nation’s capital. However, there were only a few ripples with which this slow-moving river of my life was undulated for a day just a few months back.

I was traveling that day in the Delhi metro like I did, often, amid the sweaty, noisy cacophony of my co-passengers. I managed a place to stand among men, women and children of all ages and sizes who kept staring with curious eyes at me, my attire, my braided hair, my make-up laden eyes and face. Suddenly, in the crowd, my eyes followed the contours, the dreamy eyes, the conjoined eyebrows, the slender body of a young woman seated in a close corner, trying to feed milk to a prattling toddler boy. She was humming a familiar Hindi song and shaking his toy rattle when the boy threw sudden tantrums, in her effort to pacify him. The song was a very known one, just as her voice was. Just then, the milk bottle of the toddler slipped from her hands and dropped on the ground, and within seconds, when I picked it up from there and shoved the crowd to give it to the woman, those familiar, dreamy eyes met mine for some seconds, and crushed me from deep within.

“Nitu, my sister, my jaan!!” My body, my mouth, my whole being was trembling with a mad ecstasy, compelling me to call her out loud and give her the tightest hug, a hug that would bridge the years and miles of our distance. In my shoulders, I was carrying the same ladies bag that I had hijacked from her twelve years back on the fateful day I left home…I had maintained it like a precious asset, using it scarcely and with utmost care. The moment my eyes fell on hers again and tears had started to well up on both our eyes, I had made up my mind…I had to get down from the train right now, no matter what the station was….I had been an expert in farewells and there was no looking back, lest the filial ties made me more vulnerable, incapable of breaking my earthly shackles.

As I pushed through the crowd and got down the train in a desperate bid to flee from the scene, I felt Nitu’s supple hand clutch one of my shoulders, in her arms, her toddler son resting comfortably.

“Veeru, I know it is you…don’t run away from me, I beg you. I am your sister Nitu, talk to me for once.” She pleaded, the kohl in her eyes smudged with tears.

“What have you done to yourself, Veeru?” Her helpless eyes asked me.

“Call me Rani, please, I have a new life now.” I beseeched her.

Holding my hand with earnest longings, she flopped down on one of the benches at the crowded Rajiv Chowk metro station, her son playing zestfully with the multicolored bangles that I wore in my hands.

“We searched for you all over Jalandhar, Veeru, and Baau jee left no stone unturned to look for you in all the places he thought you could have eloped to. He beat me and coaxed me into revealing your whereabouts, since he knew how close we were, but I remained silent. Even I didn’t know where you had gone, isn’t it, but it was hard to convince them. After a year of frantic searching, he gave up. In his death-bed, last year, his old eyes shed futile tears, craving to see you for one last time.”

“Baau jee, no more?” I gulped the lump in my throat, but more tremors were about to ravage my soul soon.

“Amma too, even before Baau jee.”

“Amma too?” I was gulping the poison of bitter truths, my head reeling.

“Yes, she was sick since you left, and when the news of Jaspreet’s death reached us, she couldn’t live any more.”

“Jaspreet?” I quivered, about to collapse. “Jaspreet had given birth to two daughters, and during her childbirth for the third time, in the hope of a son,there was no hope she would survive. But her in-laws wanted a son, at any price….”

The stillness between us was choking us. After a while, Neetu spoke again.

“We did both their funereal rites in Chandigarh; we stayed there for five years, after I had been sold off to a rich Seth jee who had taken a fancy for me. What else could they do, tell me, in their desperation to manage dowry for my elder sisters’ wedding? At least they have been married and settled, and Seth jee has provided well for me. I am going to meet him today in his furniture store in Connaught Place with my son, he was asking about him on the phone and wishing to see him badly.”

In my heart of hearts, I could picture the story of Nitu’s life very well, the quagmire where she was stuck and could never free herself. I was shredding myself into pieces, the tragedy of my own family, the chunks and pieces of the memories of my sheltered life with them many years back stabbing my soul, killing me mercilessly. But I was Rani, the Queen bee, the failed son, the betrayer brother, the tormented woman trapped inside a castrated man’s body who had traded one cage for the overwhelming pain of the other. “Abstain from all family ties, once and for all.” This was part of our mantra, the day I was initiated into the rituals of being a eunuch.

I had to part with her, albeit forcefully, but just before running away from them, the toddler clasped my hands again, trying to pull my bangles from my hand. I couldn’t help giving a peck on his cheeks. It gave me an unbridled sense of joy to hold him close to myself for some seconds, as I have held the newborns after my dance performances. While bidding adieu, I asked Nitu his name.

“I named him Veer, after you, as I missed you so much.” She uttered, amid her muffled tears, clasping my hand for one last time before setting me free.

…..My interview is over now, so is the pack of beedis I was intent on having all the while. The young reporter girl and her crew members hug me with enthusiasm. They celebrate their grand success in shooting my story at a go, without interruptions. Only a few days back, the Supreme court in India had recognized our clan as a third gender. The nation was now obliged legally to see us as a marginalized group, the newspaper had reported, and I had read it out to Rupa in our small, cozy den.

But what would that even mean? Was there now hope against hope, that we would find a door somewhere, open it, and claim our rightful places in the universe?

Freed from the TV crew, I walk out into the open city streets. The red, yellow neon lights in Connaught Place, the heart of the city wink at me, and the traffic grows wilder every moment. I walk in giant strides and mingle with the crowd, a transgender, fractured between my lost life and my new birth, like pieces of an unsolved puzzle.

(image source: Indiawest.com)

(image source: Indiawest.com)