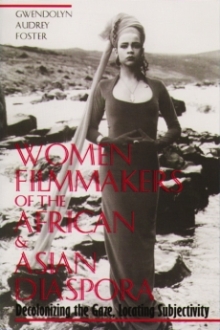

The Cover page of ‘Women Filmmakers from the African and Asian Diaspora’ by Gwendolyn Audrey Foster

Women of color are everywhere today. Be it the stupendous creative world of poetry or provocative fiction and nonfiction literature that is breaking the boundaries, be it the world of innovative filmmaking in respect of world cinema, they have been there, done that, and conquered hearts.

Looking into the history of world cinema, it is imperative that we take into account the immense contribution of talented women filmmakers of Africa and the African Diaspora who have made a mark with their innovative filmmaking. Not only are they challenging old cinematic prescriptions, they are also using their superior art of cinema to create and establish new visions of their people and the world.

The journey of black women filmmakers began as early as 1922 when Tressie Saunders, a black woman director made the exemplary film ‘A Woman’s Error’. It was the first attempt of its kind in that era to “decolonize the gaze and to ground the film in the black female subjectivity”, as the author Gwendolyn Audrey Foster has pointed out in her book ‘WOMEN FILMMAKERS OF THE AFRICAN AND ASIAN DIASPORA: DECOLONIZING THE GAZE, LOCATING SUBJECTIVITY’. However, today even after a long history of evocative work, black women directors have had a long, slow path to the director’s chair, where only a handful of black woman filmmakers have been able to break through the racial barriers in Hollywood.

However, let’s not talk about Hollywood here, but look into how these women have been received in respect of world cinema. In fact, filmmaker Julie Dash (originally from New York City) had long ago won the Best Cinematography Award with her much acclaimed film “Daughters of the Dust” at the 1991 Sundance Film Festival. On the other hand, Cheryl Denye from Liberia had received worldwide fame and accolade with her film The ‘Watermelon Woman’ (1996), which happened to be the first African American lesbian feature film in the history of world cinema. Another Black woman Safi Faye has to her credit several ethnographic films that brought her international acclaim and earned her several awards at the Berlin International Film Festivals in 1976 and 1979. Besides, there are independent black women filmmakers like Salem Mekuria producing documentary films focusing on native women from Ethiopia and on African American women in general.

In 1989, Euzhan Palcy became the first black woman to direct a mainstream Hollywood film, ‘A Dry White Season’. In spite of all this success, it is still true that the state of things isn’t all that rosy for African American women filmmakers. A documentary named “Sisters in Cinema’ by Yvonne Welbon has tried to explore why and how the history of black women behind the camera has been made strangely obscure in all of Hollywood.

“Sisters in Cinema’ happens to be the first and a one-of-its-kind documentary in the history of world cinema that attempts to explore the lives and films of inspirational black women filmmakers. In fact, the 62-min documentary by Yvonne Welbon, “Sisters in Cinema” came up in 2003 to commemorate the success and the colossal achievement of black women filmmakers throughout the ages. The film attempted to trace the careers of inspiring African American women filmmakers from the early part of the 20th century till today. As the first documentary of its kind, ‘Sisters in Cinema’ has been regarded by critics as a strong visual history of the contributions of African American women to the film industry. “Sisters in Cinema”, they say, has been a seminal work that pays homage to African American women who made history against all racial, social barriers and odds.

While being interviewed, the filmmaker Yvonne Welbon admitted that when she set out to make this documentary, she had barely knew there were any black women filmmakers apart from the African-American director Julie Dash. However, in pursuit of seeking those inspirational directors, she set out to explore the fringes of Hollywood where she discovered a phenomenal film directed by an African American woman Darnell Martin. Apart from that film ‘I Like It Like That’, she discovered only a handful of films being produced and distributed by African Americans. Thus saying, the monopoly ofHollywood by white filmmakers, producers and distributors inspired her in a way to travel the path of independent filmmaking. Surprisingly, here she uncovers a wide range of really remarkable films directed by an African American woman outside of the Hollywood studio system and thus she found out her sisters in cinema.

Within the 62-hour documentary, the careers, lives and films of inspirational women filmmakers, like Euzhan Palcy, Julie Dash, Darnell Martin, Dianne Houston, Neema Barnette, Cheryl Dunye, Kasi Lemmons and Maya Angelou are showcased, along with rare, in-depth interviews interwoven with film clips, rare archival footage and photographs and production video of the filmmakers at work. Together these images give voice to African American women directors and serve to illuminate a history of the phenomenal success of black women filmmakers in world cinema that has remained hidden for too long.

A few years back,in October 2005, there has been the ‘Eighth Annual African American Women In Cinema Film Festival’ in New York City. It was another remarkable event that showcased exceptional feature and documentary films as well as short films made by African American women filmmakers like Aurora Sarabia, a fourth generation Chicana (Mexican-American) from Stockton, CA, Vera J. Brooks, a Chicago-based producer, Teri Burnette, a socialistic filmmaker, Stephannia F. Cleaton, an award-winning New York City newspaper journalist and the business editor at the Staten Island Advance, Adetoro Makinde, a first generation Nigerian-American director, screenwriter, producer, actress, among others. Also, from February 5 to March 5, 2007, there has been the celebration of the Black History Month by the Film Society of Lincoln Center & Separate Cinema Archive, in which the center presented “Black Women Behind the Lens”.

A seething documentary, “Black Women Behind the Lens” celebrates the uncompromising cinematic labors of love created by a group of brave African-American women. Gifted with rare determination and undaunted spirits, these black women filmmakers were committed to speaking truth to power while offering alternatives to the stereotypical images of black women found in mainstream media. They resorted to Guerilla filmmaking, an artistic rebellion in the face of the long established network of Hollywood and have challenged old cinematic perceptions, using their art to erect new visions of their people, their heritage and their world. Noted theoreticians, sociologists, women writers, directors are saying that it is good to know that women filmmakers of Africa and the African Diaspora are challenging old cinematic prescriptions and creating their own visions in the cinema they love to make.

However, while a significant number of women in Africa and here in the have been able to carve out successful careers in filmmaking, the hurdles are particularly daunting. The problem, says Elizabeth Hadley, the chair of Women Studies at Hamilton College in Clinton, N.Y., is not particularly about black women making films, but the issues of marketing, distribution and funding. As a result, the majority of these women are finding money independently and working on shoestring budgets. However, all said and done, it is enough encouraging to know that at least some of these women are daring to decolonize the gaze of Hollywood and to ground their films in black female subjectivity. Any attention or recognition that comes when these women desire to communicate their ideas about black people’s history, heritage, with an emphasis on women’s experience, must be welcome!

P.S. This article was originally published at Yahoo Voices, titled ‘Black Women in Filmmaking: The History and Success of Black Women Filmmakers of Africa and the African Diaspora’.

http://voices.yahoo.com/black-women-filmmaking-346287.html